Suicide Postvention – Crisis Response Summary

Summarized by: Sana F. Ali, MD

Suicide is a human condition. As such, Muslims are not immune to mental health challenges, mental illness, and suicidal ideation.

The Institute for Muslim Mental Health coordinated and hosted an emergency Meet the Expert Pro-Series webinar in response to a mental health crisis in the Muslim community. The Pro-series webinars are geared towards Muslim mental health practitioners and community faith leaders.

This article summarizes the key learning points of the live webinar by mental health clinician and academic researcher Dr. Rania Awaad.

Topic: Suicide Postvention in the Muslim Community – Community Interventions After a Suicide Occurs

Objective: What to do after a suicide occurs and how to serve in a situation of sudden loss (Postvention Response)

Important definitions:

- Suicide Prevention includes the steps taken to reduce the risk of suicide. However, in the aftermath of a suicide, our focus should be on postvention and community healing.

- Suicide Intervention relates to the direct effort to prevent a person from taking their own life.

- Suicide Postvention includes the steps people take to respond to a suicide after it happens. These strategies emphasize the need to save lives and help ensure that community members have access to appropriate mental health care services. After a suicide happens in a community, mental health professionals shift their focus to preventing suicide contagion.

Goal – Response

- Suicide Contagion aka copycat suicides is a well-documented phenomenon in which people’s direct or indirect exposure to suicide increases their risk of dying by suicide too. Suicide contagion can result in suicide clusters. Often affects youth.

Goal – Prevention

- Suicide Clusters are when multiple suicides occur in close proximity.

Goal – Prevention

Preventing suicide contagion is one of the top priorities of a postvention response.

Postvention Model:

Postvention Response Goal: To reduce suicide risk

↓

To support the loss of survivors and community members

↓

To return to routine and community

Short-Term Response: Day 0 – Day of Event

- Identify

- Who are the bereaved?

- Who are the most immediately impacted?

- Activate

- Activate the Crisis Response Team (CRT)

- Mobilize mental health professionals who can step up and step in

- Manage Media

- Media may sensationalize, overshare, and inadvertently further stigma and harm

Days 2 – 14 – Follow Up

- Follow up with the family regularly

- How can you help with funeral arrangements, food, chores, etc.?

- The most bereaved may be in shock and unable to fully grieve

- Support is needed even after the attention is gone

🗒 People in a suicidal state often have distorted thought processes and pre-existing mental illnesses are implicated in over 90% of suicide cases.

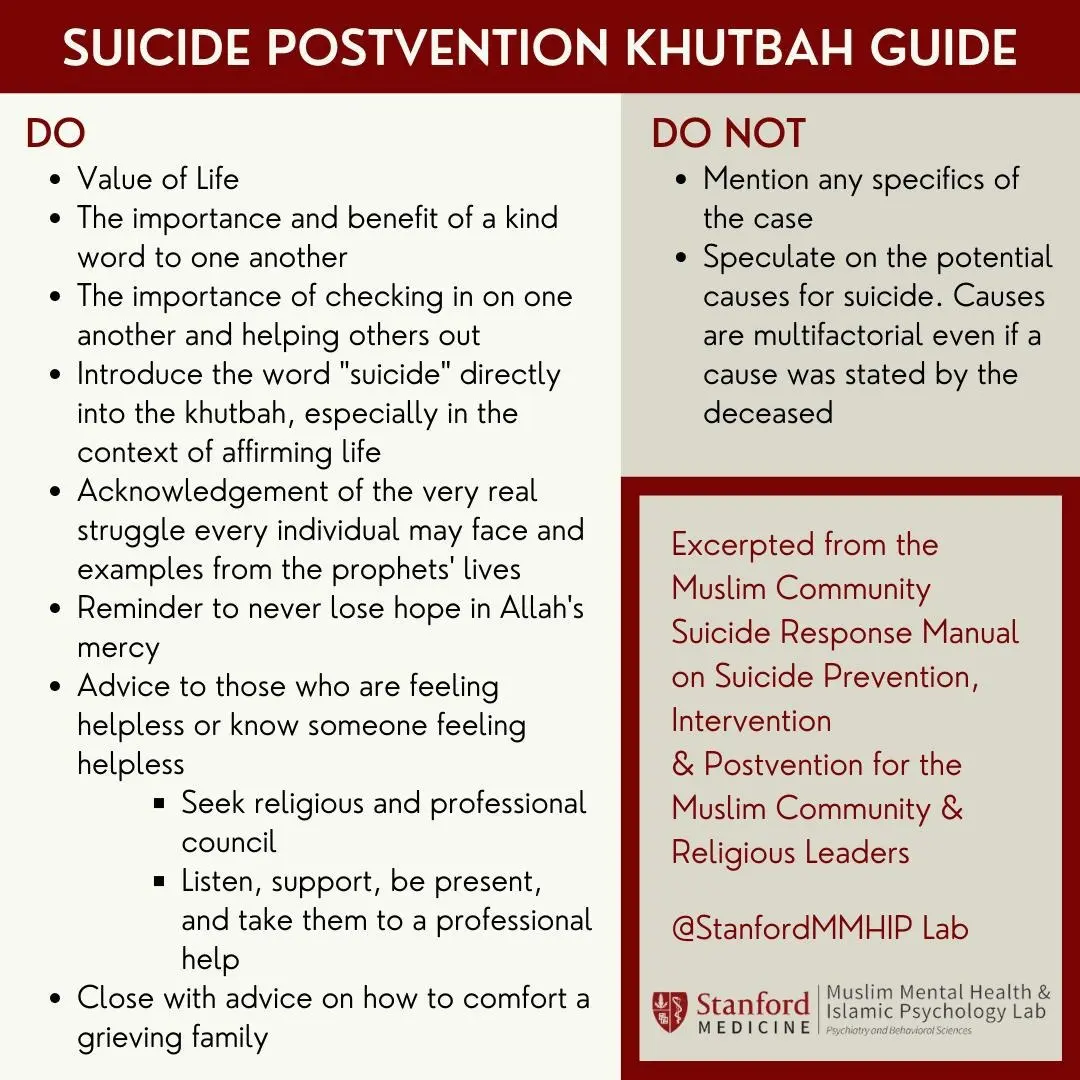

Postvention Khutbah

Do we use the term “suicide” or not? Best practice guidelines say YES. Affirm that their emotional response is very real and encourage seeking professional support.

Do not speculate on the spiritual implications of suicide. It is inappropriate to discuss whether you believe they deserve heaven or hell.

Janazah

It is the role of the community leaders to shift the conversation from “What’s going to happen to the deceased?” to “How can I support my community in this time of hardship?”

The community should ask themselves “What is my role in this situation?” and “What is not my role in this situation?”

People are essentially contending with asking “How do I move past the grief I am feeling and the uncertainty of what the deceased is facing in the hereafter?”

Stating that suicide is haram may prevent people with suicidal ideation from acting upon it. However, this concept is helpful in suicide prevention rather than suicide postvention.

Religious leaders may choose not to lead the janazah but may designate someone else for it.

“Among those who came before you there was a man who was wounded and he panicked, so he took a knife and cut his hand with it…until he died.”

- Prophet Muhammad (PBUH), Narrated by al-Bukhaari, 3276; Muslim, 113.

The Prophet (Pbuh) refrained from leading the janazah, but he permitted the Sahaba to offer janazah.

Moral: Do all of the last rites of janazah even in suicide.

Memorialization

The goal should be to balance the need of the community to grieve while also avoiding the glamorization of death.

Focus on the future– Not the present, and not the past.

🗒 Suicide is NOT an anomaly. It is endemic.

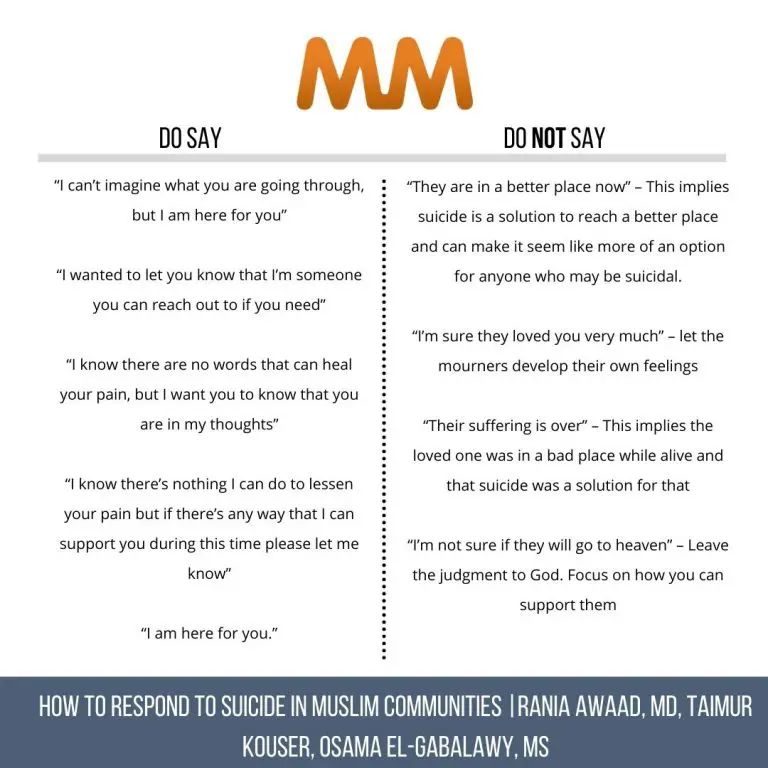

What to Say to Suicide Loss Survivors

Listen First – Let them lead. Do not project your emotions onto them. Allow them the opportunity to communicate what their feelings are.

Let them Lead and Find Words – Allow people to process their emotions in their own words and on their own time.

Ease Guilt – Speak of Qadr or Divine Power. Remind them that sometimes we do not have answers, but we can grieve and heal without the answers.

Reach Out – Check in consistently, both in the short term and long term.

Support & Encourage Care – Integrate Islamic principles.

Sympathize – Express sympathy as you would for any sudden death.

Spreading Risk Factors

Sharing explicit details of the suicide may normalize it.

Refrain from reporting specific details (method) which may promote and sensationalize the death.

Resist discussion in social places as your personal opinion may be perceived as a mental health professional opinion or the legal authority.

Refer to Reportingonsuicide.org for suicide guidelines.

Sharing suicide notes under the excuse of “information/awareness/education” is harmful.

🗒 Even if the deceased outlines the reason for their suicide, as mental health professionals, we know suicide is never one thing–it is multifactorial.

Social Media

Any social media posts from the official accounts regarding the person who has passed should be made with the consent of the family and sensitive to their desires.

Prioritize the family’s wishes and receive their consent even for well-intentioned actions, i.e., organizing a fundraiser, vigil, etc.

🗒 Postvention in and of itself is preventative work.

Our Role

We as a Muslim mental health community have a lot of work to do. As a nonprofit organization, the Insitute for Muslim Mental Health (IMMH) can provide resources and professional mentorship. IMMH is a professional home for Muslim mental health providers globally.

Gain access to experts, engage with professional peers, and add your professional service to a Muslim mental health provider directory. The provider directory currently spans the US and Canada and is free to the public! Become an IMMH member today.

The Stanford Muslim Mental Health & Islamic Psychology Lab has developed a robust, evidence-based, Islamically-grounded suicide prevention, intervention, and postvention manual and training. It provides in-depth, step-by-step guidance for the Muslim community and religious leaders that was developed in collaboration with Muslim leaders and suicide experts.

- Find a Muslim Mental Health Provider in your area here: https://muslimmentalhealth.com/directory/

- Access informational toolkits: https://www.thefyi.org/toolkits/

- To access Muslim Suicide Response Trainings and Manual: Maristan.org

Rania Awaad M.D., is a Clinical Associate Professor of Psychiatry at the Stanford University School of Medicine where she is the Director of the Stanford Muslim Mental Health & Islamic Psychology Lab, Associate Chief of the Division of Public Mental Health and Population Sciences, and Co-Chief of the Diversity and Cultural Mental Health Section in the department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences. She is also the Executive Director of Maristan.org. Her research and clinical work are focused on the mental health of Muslims. Her courses at Stanford range from teaching a pioneering course on Islamic Psychology, instructing medical students and residents on implicit bias, and integrating culture and religion into medical care to teaching undergraduate and graduate students the psychology of xenophobia. Some of her most recent academic publications include an edited volume on “Islamophobia and Psychiatry” (Springer, 2019), “Applying Islamic Principles to Clinical Mental Health” (Routledge, 2020) and an upcoming clinical textbook on Muslim Mental Health for the American Psychiatric Association. She is currently an instructor at the Cambridge Muslim College, TISA and a Senior Fellow at Yaqeen Institute and ISPU. In addition, she serves as the Director of The Rahmah Foundation, a non-profit organization dedicated to educating Muslim women and girls. She has previously served as the founding Clinical Director of the Khalil Center-San Francisco as well as a Professor of Islamic Law at Zaytuna College. Prior to studying medicine, she pursued classical Islamic studies in Damascus, Syria, and holds certifications (ijāzah) in Qur’an, Islamic Law and other branches of the Islamic Sciences. Follow her @Dr.RaniaAwaad

About the Author:

Dr. Sana F. Ali is a postdoctoral associate at the Yale School of Medicine. Dr. Ali conducts clinical research which explores the psychiatric co-morbidities of neurologic disease. A passion for culturally competent care and health equity underscores her clinical and research work in global mental health. She has been invited to speak at churches, Islamic schools, and university student organizations on mental health stigma, Muslim mental health, and peer mentorship. Dr. Ali serves as the Program Director at the Institute for Muslim Mental Health, where she champions personal and professional growth, mentorship, and community for Muslim mental health providers.